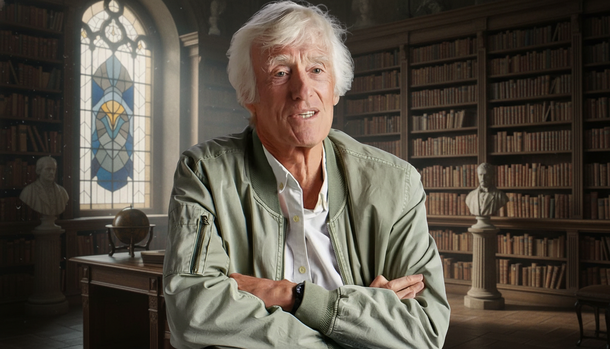

Roger Deakins’ 10 Most Visually Striking Films Ranked

Discover the ten most visually captivating films shot by Roger Deakins. Explore how his unique approach to cinematography has shaped modern cinema, from noir classics to sci-fi epics.

Few cinematographers have left as indelible a mark on contemporary film as Roger Deakins. His signature approach, eschewing obvious stylistic flourishes in favour of subtlety and emotional resonance, has defined a generation of cinema. Whether capturing the stark isolation of a desert highway or the neon glow of a futuristic metropolis, Deakins’ work is instantly recognisable, yet never repetitive.

The Art of Understatement: From Comedy to Drama

Take The Big Lebowski (1998), for instance. On the surface, it’s a comedic riff on detective noir, but Deakins’ lens brings a quiet sophistication. Los Angeles is rendered in a soft haze, echoing the protagonist’s languid outlook. Wide shots allow characters to meander through space, lending the film a relaxed yet deliberate rhythm. The bowling alley scenes, bathed in gentle artificial light, and the dreamlike sequences, which never lose their clarity, are testament to his measured touch. Even the most mundane interiors are carefully composed, letting the humour breathe while maintaining a distinct visual polish.

In The Shawshank Redemption (1994), Deakins’ restraint is equally evident. The prison’s vast corridors and rigid framing evoke both the enormity and the claustrophobia of incarceration. Natural light softens the harshness, humanising even the bleakest moments. As hope gradually seeps into the narrative, the visuals open up, culminating in iconic scenes such as Andy’s rain-soaked liberation. Here, Deakins trusts in simplicity, allowing the story’s emotional weight to emerge organically.

Visual Storytelling Across Genres

Biographical drama A Beautiful Mind (2001) sees Deakins using light and shadow to mirror the protagonist’s shifting mental state. Early scenes are warm and inviting, but as John Nash’s reality unravels, the visuals grow colder and more isolating. Deakins often frames Nash alone in cavernous spaces, subtly underscoring his internal struggle. The camera remains non-judgemental, inviting viewers to observe rather than condemn.

With The Reader (2008), Deakins crafts a visual language that shifts with the narrative’s timeline. The past is rendered in soft, intimate tones, while the present feels distant and austere. Interiors are dimly lit, hinting at unspoken secrets. Faces are illuminated with care, allowing emotion to surface naturally. The result is a film where the images never overshadow the performances, but instead deepen the sense of regret and responsibility.

Darkness, Tension, and Technical Mastery

Prisoners (2013) stands out as one of Deakins’ most brooding works. The film’s visual palette—dominated by rain, shadow, and muted hues—amplifies the sense of dread. Suburban streets are rendered cold and empty, interiors claustrophobic. Light sources such as torches and streetlamps become crucial, reinforcing the characters’ desperate search for answers. Despite the bleakness, every frame is meticulously composed, revealing a haunting beauty amid despair.

In Skyfall (2012), Deakins reinvigorates the Bond franchise with bold, expressive visuals. Each location is distinguished by its own colour scheme: Shanghai’s cool blues and sharp silhouettes, Macau’s opulent golds and reds, and the Scottish finale’s moody, almost Western atmosphere. Every shot is carefully framed, enhancing the film’s exploration of identity and legacy without ever feeling gratuitous.

Epic Visions: War, Sci-Fi, and Noir

Sicario (2015) is a masterclass in tension, with Deakins using harsh sunlight and deep shadows to evoke the moral ambiguity of the borderlands. The infamous Juárez crossing sequence is suffocating, while the night-vision tunnel scenes are stripped of colour, creating an unsettling, almost alien effect. The camera’s patience draws viewers into the protagonist’s uncertainty and fear.

With 1917 (2019), Deakins orchestrates the illusion of a single, unbroken shot, guiding audiences through trenches, fields, and ruined towns with seamless precision. The night-time flare sequence transforms devastation into something eerily beautiful. Despite the technical bravado, the film’s visuals remain deeply human, heightening the emotional stakes and earning Deakins a long-overdue Oscar.

Blade Runner 2049 (2017) is perhaps Deakins’ most celebrated achievement. The film’s world is awash with neon, shadow, and drifting dust, each frame meticulously designed to evoke mood and meaning. Iconic images abound: a towering hologram, snow falling on deserted streets, and spectral figures flickering in the gloom. Deakins elevates the original’s legacy, crafting a richer, more emotionally resonant visual experience.

At the pinnacle sits The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001), a monochrome neo-noir that showcases Deakins’ precision. Inspired by 1940s cinema, the film’s high-contrast black-and-white imagery is both homage and innovation. The world is reduced to light, shadow, and form, each composition echoing the protagonist’s existential emptiness. The result is a haunting, sculpted visual journey—a true masterclass in restraint and storytelling.